1986 – The nuclear Hell of Chernobyl and the Fox of Pripyat Ghost Town

Pripyat – The abandoned ghost town

“My personal fortune was to have a good organisational and logistical talent, hence I only had to clean-up two times. The particles emitted by the reactor into the environment gave a metallic taste in your mouth. The radiation makes you feel burning inside down to the stomach, as if you didn’t drink or several days.”

Winds carried the reactor’s fission products to territories being north and western of the power plant polluting Pripyat and nearby Belarus. Pripyat was lost, though it remained to be the main base for pilots and liquidators, while organisation and management worked in 15 kilometres away Chernobyl. There, in Chernobyl’s culture palace, also the trial against the responsible was held.

At the latest when radiation protection supervisor and envoy officer Misha takes me through the checkpoints of the 30km security zone and 10km Chernobyl exclusion zone I start to shake in my boots as for the next 2 days I’ll be living in a highly contaminated area where one of the most terrible accidents in human history happened.

At each checkpoint the officer on duty has a close look at my documents as western individual visitors entering the exclusion zone are an exception. The area got decontaminated as far as possible but there’s always a chance for a nasty surprise. Since literally everything could transfer invisibly radiating elements, long sleeves and pants as well as sturdy non-open shoes with thick soles are mandatory, but also Misha wants to show me more than other visitors get to see.

Visitors? Yes, Chernobyl is a touristic attraction meanwhile being visited by some 30.000 people throughout the year. More than 95% are part of a daytrip without staying overnight. Having arrived Chernobyl village I instantly notice a blood curling noise coming from the forest. It has nothing to do with radiation or the accident. It is a sonar operating at full stretch, because of the war in East Ukraine. The noise produced by that thing is terrible.

Taking photos in the exclusion zone is not an easy thing when it comes to people. They are interesting but tough characters, so is Leonid. He asks me not to take photos as he’s heavily defaced. People like he saved our central European bums. For example the seals (divers) that dived under the reactor to drain the huge water reservoir under the power plant. They don’t live anymore. They saved Central Europe from a huge deflagration that would have been caused by the extremely hot nuclear meltdown mass meeting water.

Europe, cities like Berlin, would have received the radioactivity as if 2-3 nuclear bombs would have exploded. People like those divers are heroes. They deserve Peace Nobel Prizes, not liars like Barrack Obama (who didn’t close Guantánamo, who fuelled drone war and who spies the whole world) or Helmut Kohl (who did nothing about German Unity as Gorbachev put the remains of GDR in his hands).

But let’s get back to the accident. Such moments show important error culture is as one can have the balls to concede that something went wrong or start lying. Unfortunately 90% of humanity take a decision for being dishonest, like the powers of Chernobyl who kept painting a pink “all is good” picture until the evening of April 26th 1986.

I asked many Russians and Ukrainians, some of them living in Berlin, how they perceived the event. In the first days each of them did not have a clue what was going on; something that was made use of by officials when they ordered people from all over Soviet Union, mostly men who already fathered children, into the disaster zone.

While about ~50.000 people inhabiting Pripyat and later further ~115.000 people living in Chernobyl’s proximity got evacuated from the hastily set up exclusion zone, some 600.000 to 800.000 people went into the battle against an invisible enemy. Those people confined radioactivity and contaminated objects. They filled up the burning open reactor and drained the water reservoir underneath the power plant. They prevented the superhot melted nuclear mass from breaking through into the underground. We, also us Central Europeans, owe those people a lot.

There are only a few nations in the world having such an extraordinary willingness to make sacrifices like Soviet Union and Russia, as, no matter if voluntary or commanded, working in the reactor’s periphery meant death. What being exposed to radioactivity meant to an individual’s health is hard to say. Leonid is lucky, he is still alive, but many of his colleagues died already, officially from natural diseases like heart attacks. Shamed be he who thinks evil of natural causes of death if the background is an actually radioactive one.

Before reaching the power plant we drive through the former villages Salisya and Kopachi. Salisya is abandoned while Kopachi was buried under piles of soil. Each pile is decorated with a warning sign “Caution! Radioactivity!” With hot spots emitting 13-14 µSv/h this area is already profoundly contaminated.

We have a short controlled side trip though and see the local Kindergarten, but only because the Kindergarten building itself is ok radiation-wise. Walking an hour along the Kindergarten path leading through the forest would mean to absorb so much radioactivity like a human should actually get only during a day. Staying there for a couple of minutes is ok though.

My way also leads along the ruin of reactor 5. Its construction as well as erecting nearby cooling towers was stopped when the accident happened. Radioactive dust is all around in there. But nature claims back what belongs to it, hence a colony of gulls and terns indulges in nesting at the bottom of the reactor. From there it’s not far away to the power plant’s canteen, where we get an abundant meal for a few Hryvnas only.

On the way back from the bridge over the cooling water channel we see giant catfish. Their huge extent doesn’t have anything to do with radioactivity but with very good feeding.

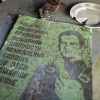

Not far from the bridge are the buildings of power plant administration and the memorial to honour pilots and liquidators. The central monument of the memorial is a statue that once stood in Pripyat. Also the dead fire fighters, who were on the accident site first, have a memorial right next to the gate of the works fire service. From there it is not far away to another memorial that stands right in front of the reactor ruin 4.

There, lying dormant inside the sarcophagus, is the final good of the nuclear meltdown, something like a little sun. One gram of this mass radiates with more than 4 billion Becquerel. Food gets declared as radioactive burdened at ~350 Becquerel. Despite heavy walls, steel and concrete you shouldn’t stay there too long.

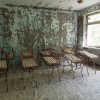

Then we head on to Pripyat ghost town. On the way is the picturesque town sign and yet another checkpoint. Again we have to show all documents we’ve got. First stop in Pripyat is the former central square with the town’s supermarket, culture palace “Energetic” and hotel “Polissya”; a backdrop that should be quite familiar to the guys who played the sniper mission in Call of Duty 4.

Already at the first stop one thing becomes apparent: over the years Pripyat was subject to vandalism as virtually everything got destroyed knocked over. That doesn’t really look like a city that had to be abandoned head over heels. Militia even has to be on patrol due to not few metal thefts. The metal is often contaminated and must not get in circulation in no case. However, some 3 weeks ago on a scrap yard in Kiev contaminated metal from the Chernobyl exclusion zone appeared.

Behind the culture palace the second Pripyat icon can be found, the amusement park that never started operations. The square between bumper cars and Ferries wheel is a radiation source as well as here once helicopters landed to stash fire extinguishing sand, boron as well as lead blocks. During their flight above the open reactor to unload their freight they got terribly contaminated. The moss transports those radionuclides back to surface again. Generally the radiation leading layer is some 20-25 centimetres deep underground. Only due to that circumstance we’re allowed to move around freely.

Actually I like to portrait abandoned places in winter or spring when vegetation isn’t too lush, but Pripyat is a green hell these days. However, that is a symbol par excellence as it shows how strong nature can claim back what belongs to it. The cherry on that cake is a fox walking past us cool like a cucumber. It even lies down in the shadow of Pripyat’s Ferries wheel and has no problem at all to become photographed.

It is not the only mammal living in the exclusion zone. Wild boars, wild cats, bears and even moose got sighted here and the whole place is teeming with birds, from blackbirds, tits to Eurasian jays. If I would buy into the Russian superstition that the call of a cuckoo stands for the remaining years of my life, then I’ll be a horror for my pension insurance as I’ll stop counting up at ~400. Constant like a machine the bird calls through the ghost town.

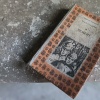

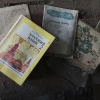

We go further and visit the indoor swimming pool, the police station with its prison and contaminated trucks in the backyard. Also we have a look at the school of third district where hundreds of gasmasks are spread all over the place. Let’s be frank: most of the motifs and images are staged and composed eye-catchers. I don’t touch that stuff though as too much dust is involved. Since you can wash it off it is still “sort of ok” to become contaminated externally, but inhaling dust or eating contaminated food is the worst that can happen. That’s the way how 131iodine or 90strontium gets deposited in your body. Greetings from thyroid disease and leukaemia!