Dasht-e Lut – World’s hottest Desert

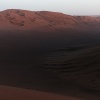

Iranian Dasht-e Lut is the world’s hottest desert. In 2016 satellites measured unbelievable 78.2°C, what is the highest ever calculated surface temperature on Earth. Our planet’s heat pole is a UNESCO World Heritage and impresses with sand dunes being up to 450 metres high as well as the rugged surreal rock landscape of the Kalouts.

Dasht-e Lut – Some like it hot

Fortunately one doesn’t sense much of the 78°C this morning when the team of Kalout Desert Travel around Arman and Mina arrives our desert lodge 8 o’clock. Already from far away we could hear their jeeps. In the next days they will take us deep into the hottest desert of Earth. How those 78.2°C get measured? Well, there’s surely nobody driving out to ram a medical thermometer into the desert’s back. ;-) In a world full of technology satellites do that job. One of those Earth trabants is MODIS, a long-known companion for us volcano enthusiasts as it helps us to monitor lava lakes like Erta Ale.

Such a singeing heat is only possible in Summer. It is winter now and the more than 166.000 km² large desert (دشت لوت) Dasht-e Lut gets covered by a thick cloud layer; as if the usually merciless sun allows us some short time of clemency. That grain of air moisture is enough though for some audacious plants and insects to survive in the desert. Among them is the desert fox, small flies but also a gross large white spider species. Its sight rockets the octopod easily into the Top 10 of the world’s most ugly animals and makes childhood nightmares come true.

Well, we won’t really “see” the world’s hottest spot as it is located in northern central Lut while we head southeast, to where giant star dunes rise up some 450 metres and to where Kalout rocks pile up more than 70 metres high.

Millions of years old sediments

Kalout is Persian for Yardang. Yardang again is Chinese and the geologic term for streamlined bedrock protuberances and remnants of millions of year old deposits of loess and silt being carved by erosion and corrasion. Meaning a surreal looking geomorphological rock formation with a name going back to 1903, that is its first sighting and documentation.

Back then Sven Hedin explored Chinese Lop Nor desert and his records describe a similar rock formation being named Yar by local Uighurs. The majority Iran was once a part of the sea. Due to tectonic movements it was cut off and the seabed fell dry. Then the land got put through the erosion and corrosion mill and mainly it was the wind that ground the rocks and blew away the sand that’s now creating large dunes.

That’s exactly where our trip leads us to, the large Dasht-e Lut dune area very close to Pakistan-Afghan border, where we spend the night camping in the shadow of a giant sand pile. The eastern border region is everything but harmless as armed opium as well as human traffickers are up to quite some mischief. Moreover that territory got mined by Iranian military to fight smuggling.

Before reaching the dunes we need to cross the unspectacular and pretty dusty Dasht-e Lut lowland of Hamada. If anyone ever had the idea of Earth being flat then that thought must have been come up over here… Hamada’s flatness is so flat that even for me, after having seen Danakil desert as well as African salt pans, it’s unbelievably even.

There is nothing, really nothing, not even a little heap of sand. In the far distance we are allowed to see some mountain ranges though. Only God knows where the heck those striped little flies covering our lunch sandwiches come from.

Nocturnal visitors

Yet there’s sun, hence we quickly put our tents up. Yes, we’re sleeping in tents as winter nights in Dasht-e Lut can become pretty cold as well as there are only a few people worldwide fancying a severe sand face peeling while they sleep. While Arman kicks off the camp fire to grill some excellent kebab – turning out to be the best I had during my whole Iran travel – we climb the dunes around to get an idea what our surroundings look like.

The clouds move out and the setting sun makes the sky literally exploding in all shades of orange, red and violet. Now we are very lucky to have had a cloudy day and even some low stratus in the desert. The sun has barely disappeared when a remarkably chilly wind freshens. We’ll enjoy it all night long as it shakes our tents…

The morning after we wake up before dawn starts. The wind is still there, cold and strong. In the twilight we get a glimpse of curious desert fox before we climb the dunes again. Priska Seisenbacher and Andreas Schörghuber from In Extenso as well as Alex and I sit on a dune top ridge getting peeled by flying sand to wait for the sun to appear and Dasht-e Lut to wake up.

Sunrises as well as the sunsets in the desert are extremely rare as picturesque as Instagram fakes want to make us believe. It needs conventional or local dust clouds to reveal or better to say to mirror the sunlight colours. Since those clouds are often missing, well, things in the desert are commonly more dull than vibrant. That lesson I had to learn since I climbed dunes first in Moroccan Sahara at the Erg Chegaga.

Kalouts at full moon and the desert star sky

When putting down our tents we notice that a small, about 4 centimetres long scorpion made itself feel at home under the ground tarp. Final Destination alike thoughts like “If that guy would have poked through the bottom…” go through our minds. Though it is interesting to see how unbelievably transparent that little desert bugbear is.

Arman takes us on a Dasht-e Lut fun ride with his lovely Toyota Hilux, a splendid car I could drive myself back in Southern Africa. When driving over a dune ridge the second jeep got terribly stuck in a dune; even two tires de-aired. Professionally and cool as Fonzie Arman repairs the car making it possible to reach the second camp site in southwestern Central Lut where hundreds of surreally shaped and very photogenic Kalout rocks await us.

The setting sun as well as its rise stage that scenery and its contrasts majestically. Even at night we don’t find sleep, not because of scorpions but becaus of the light and vibe of an almost full moon. Being brought together lunar light and our headlamps illuminate the Kalout rocks against the star sky. Shooting such photos isn’t easy though when one wants to have stars and not their trails in the picture. Taking one image needs more than 20 minutes.

Again we wake up early to eyewitness how Iran’s largest desert, soaks up the first light of a new day. Yet again the veil of dust at the horizon allows the sidelight only to boost the sand colour of the rocks. As usual in the desert the morning is far away from a colour explosion in the sky. Chemistry is right among us travellers, hence we walk our way together as well as individually to capture the morbid charm and beauty of Dasht-e Lut onto digital celluloid.

Serpentines and mosques

The salt pans of Dasht-e Lut plus thousands of years old dry rivulets as well as the light and eating dust reminds me a lot of my journey into Namib desert in Namibia. Fortunately here in Iran there are much less encounters with other tourists. I would even say that we’ve been the one and only humans far and wide within hundreds of square kilometres. Well, maybe excepting for the one or another guy smuggling drugs or humans.

Unfortunately we have to make our way back towards Shahdad soon, or better to say toShafiabad. On that way we reach the valley of mosques at noon. Instantly I get flashbacks to Istanbul as indeed the far away Kalout rocks look as if Ottoman architect mastermind Mimar Sinan went wild. The large mountain tops look like domes and to boot they are surrounded by rock spires appearing like minarets. Only the muezzin’s midday call to prayer is missing.

Further along the way we make a stop at the Snake Canyon. Still thinking about the fugly white spiders eye become big when hearing such a name, but the canyon fortunately only meanders through the scenery like a reptile. The gorge is a geological witness of what happened and a Herold of things about to happen.

Even tiniest amounts of water start the process that erosion and corrasion walk hand in hand. The terrain gets some scars that on the other hand provide the wind a spot to attack. That on the other hand grinds the sediment rock until it becomes a Yardang and the blown away sand a dune. That thousands of years lasting procedure created the scenery that we were allowed to see in Dasht-e Lut.

Protection of border and natural heritage

Having barely left the desert and reached Nehbandan-Shahdad Road, a jeep overtakes us and cuts our path. Assault rifle armed men jump off to block our car and doors. For a short moment I think about my last will. Again it’s Arman who settles the situation.

He can prove the Iranian soldiers that everything’s announced, approved and that we’re not blue eyed blonde Afghan heroine smugglers. Iran is pretty serious about fighting opium dealing as well as human trafficking. Both things quite prosper since NATO “took care” of the neighbour country. Prices for opium stabilised again and human trafficking dropped from 30.000€ to 3.000€ per head, that to the West.

A last time we get up very early as sky and clouds look interesting. Andy tortures his rental car to 2-3 places we put an eye on along Nehbandan-Shahdad Road and before leaving for the desert. Slowly the sun makes it over the horizon and awakens Dasht-e Lut and its sand and earthy colours, but also my freezing toes.

Up to 2 kilometres one may drive into the desert. Exceeding that limit means quite some trouble with military, not only because of the smugglers but also due to protection of a UNESCO World Heritage natural site. The moment of farewell has come. Priska and Andy head further south while we drive the opposite way as we want to visit the lovely, almost Yemenite appearing oasis village of Nayband.

We are not only saying goodbye to each other as well as to our guides, but also to magic Dasht-e Lut desert and the time having spent there. Thanks a lot to Arman and Mina and of course to Kalout Desert Travel for letting us exploring one of the most interesting deserts worldwide.